Zimmermann: The untold story of a Nairobi estate with a German name

On these grounds stood the second largest taxidermy factory in the world

On April 12, 1971, at the Nairobi Hospital, Karl Fritz Paul Zimmermann (pictured) finally took the final bow as he succumbed to diabetes. Apart from a small filler in the local dailies, few people took notice.

Yet, this Silesian native, who served in the German army during WW1, is immortalized in a Nairobi estate.

Apart from Out of Africa Danish writer Karen Blixen, whose name is immortalized in the upmarket Karen in Nairobi, Zimmermann has all but been forgotten. Many Kenyans still wonder why a down-market Kenyan estate at the edge of Kiambu has a German name.

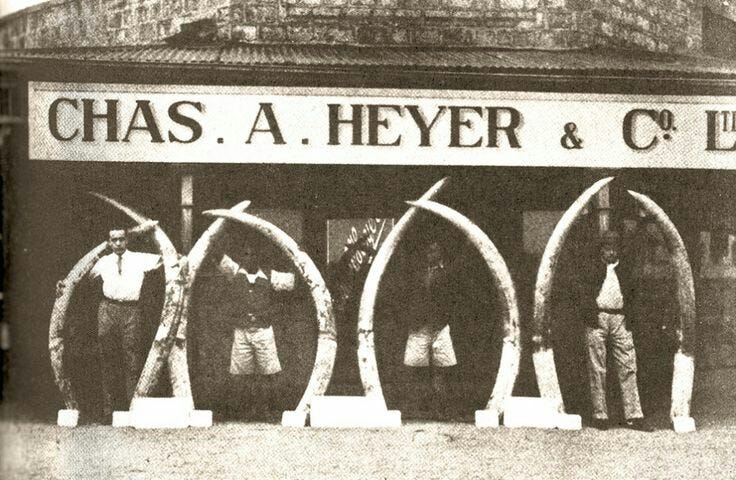

Zimmerman had arrived in Kenya in 1929 to help build a taxidermy branch for Chas A. Heyer & Co., whose owner was a German hunter who was involved in the import of Mauser sporting rifles to British East Africa. Most of these were branded Chas A. Heyer. He also ran a small shop on the grounds of modern-day MayFair Hotel.

It was after the death of Heyer on October 1, 1931, and burial in Nairobi’s Forest Road Cemetery, that Zimmermann took over the company and built his factory on the northern plains of Nairobi.

Thus, the land on which Zimmermann Estate (wrongly spelt Zimmerman) stands was owned by this German settler who built the second largest taxidermy factory in the world.

Kenya, then, was a big exporter of trophies and animals mounted for display by the rich and museums all over the world. Most of these Zimmermann products can still be seen in various sports clubs and age-old Kenyan hotels and elsewhere in museums and art galleries. State House in Nairobi also displays some of the art from Zimmermann Limited, as the company was then known.

That was before a national ban on hunting in 1977 brought the factory (above) to a halt- and perhaps ended the continued extermination of animals by trophy hunters.

Interestingly, one of Zimmermann's last projects was mounting of Ahmed, the Marsabit elephant that had been protected by a presidential decree and which still stands at the National Museums of Kenya’s exhibition gallery.

Very little is known about Zimmermann, the man. But his story is weaved within the story of Kenya as the destination for big-game hunters; men and women who made fortune in the wildlife industry as licensed poachers.

But Zimmermann was not initially part of the game-hunting dollar millionaires. He had arrived in Kenya as part of a zoology research team sent by a German University for a research project. But like many others, he not only fell in love with Kenya but returned in 1929 to found Zimmermann’s Ltd (Taxidermy).

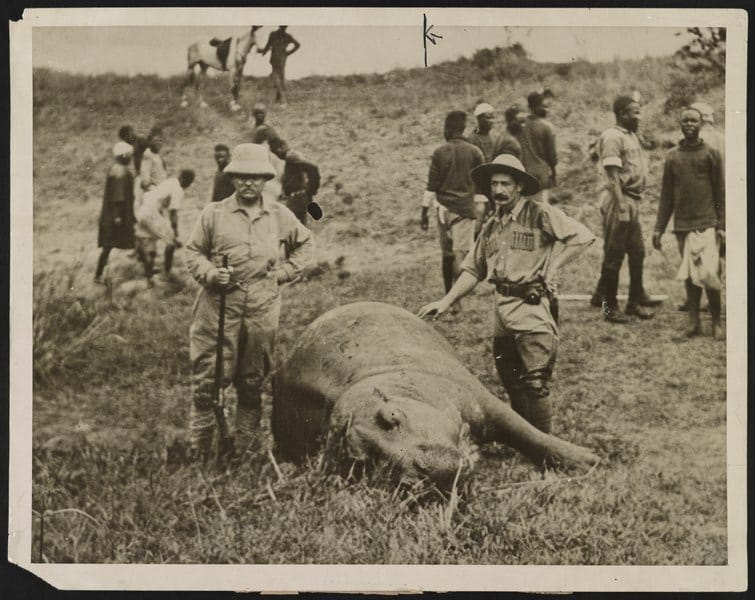

Kenya was known worldwide for the millions of animals that roamed in the expansive plains and had attracted world-famous hunting safaris sponsored by the Smithsonian Institute. Among the biggest collectors remained former US President, Theodore Roosevelt, who later helped build the Panama Canal when he became President. His escapades in Juja, Kapiti Plains and Congo are well documented in his book, African Trails and in the picture below Roosevely (left) had just killed a hippo.

With all these demands for trophies, Zimmermann acquired land next to River Ruaraka where he also built a leather tanning factory. By then, it was far from Nairobi and the obnoxious smell from the tannery would bother no one.

As big game hunting prospered during the colonial period, Zimmermann Ltd fed the insatiable appetite of princesses, kings, queens, presidents and museums. It was one of the country’s main exports apart from coffee and tea. Private galleries would snap animal trophies as they rolled out of the factory and every week truckloads of dead animals would be offloaded at Zimmermann.

In 1970s, Phillipines President Ferdinard Marcos gave Zimmermann Ltd a huge order to make mounted animals for museum in his country.

Records show that Zimmermann used to make various trophies. There were full-size mounts of large mammals like lions, kudus, giraffes, displayed from neck up, rugs of Zebras and other animals and elephant tusks.

Zimmermann also made beer bottle-openers from warthog tusks, handbags from elephant ears, stools from elephant’s rear-feet, bracelets from the hair on elephant tails and pendants from lion claws.

They did everything any enthusiast ordered: “We have even turned buffalo scrotum into tobacco pouches with zippers,” one of its general managers, Peter Wain told Los Angeles Times in 1973.

By then the company was doing taxidermy work for more than 400 safaris a year, according to records.

“We were the second largest taxidermy company after the Jonas Brothers of Denver Colorado,” Tim Nicklin one of the last employees told me in Nairobi some years ago. Tim estimated they had a workforce of about 100.

“We used to mount an average of 30 heads a day and two to three fully mounted animals.”

A lot of these were lions, wildebeests, and buffaloes.

At times, some American taxidermists would ask Zimmerman to do the tanning and ship the skins to the US for mounting while others would have all the work done in Kenya.

The Italians for instance were in love with buffaloes. “They have a thing about buffalo. I don’t know if it’s because they are effeminate, and they want to show their manhood!” Mr Wain once told Associated Press.

“The only people I talk out of work here is the old duck who wants her pet Alsatian mounted…For heaven’s sake, after enjoying the pet for 22 years, you don’t want it stuffed in a corner of the room. That’s bizarre as far as I am concerned”.

In 1969, Ken Kertell, a director at Zimmerman told Associated Press: Taxidermy is an art you see. You can’t put a dead animal on a conveyor belt and wait for it to come out the other end as a lifelike model. Everything has to be done by hand.”

And Zimmerman Ltd managers did not hide the fact that they were after dollars. Kertell once said: “We are not in this for fun, we are in it for money. But I don’t want you to get the impression we’re in the slaughter trade. We don’t look at it that way.”

In 1977, after 33 years of raving success, Zimmerman’s Ltd was given months to close shop following the ban on hunting. The government also ordered all licensed hunters to turn in their weapons to the Central Firearms Bureau.

It was the end of Zimmerman Ltd and since he did not need all that land, he sold it and from these emerged the modern day Zimmerman.

Fantastic piece you've put down John Kamau. As usual, your articles meet the seldom-reached threshold for journalism in Kenya. Keep them coming!

Great article! I visited the Zimmerman factory shop in 1975 with my Mom, who bought me a pair of black leather sandals. I remember having nightmares of the grotesque snarling animal heads and the elephant stools.