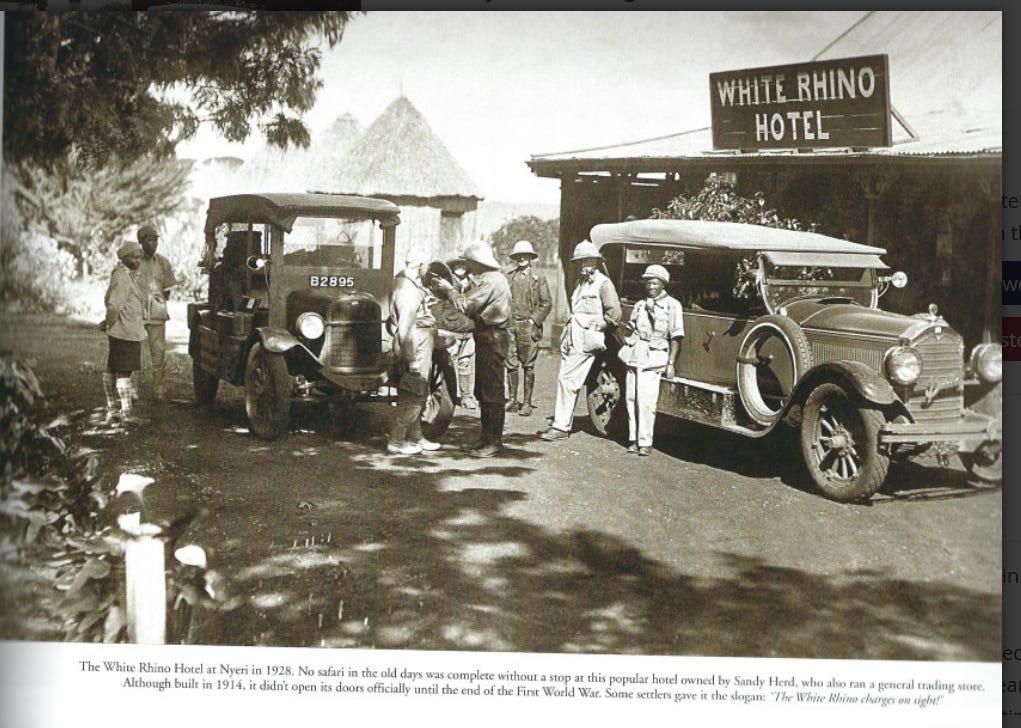

When White Rhino Hotel in Nyeri was a site of colonial privilege

The story of White Rhino Hotel allows us to interogate the making of a colony

The old White Rhino Hotel stood not only as a beacon of hospitality in colonial Nyeri but also as a stark symbol of white privilege in the early 20th-century Kenyan highlands. Designed and operated in the mould of British colonial society, the hotel was a space meticulously curated for European settlers, officials, and adventurers, offering them a familiar enclave amid the vast African landscape.

With its expansive verandas overlooking the undulating plains, polished wooden interiors, and a dining room that served hearty British fare, the hotel recreated a semblance of "home" for its exclusively white clientele. It provided not only physical comfort but also social reassurance—a place where the colonial elite could retreat from the harsh realities of settler life and reinforce their sense of status and belonging in an unfamiliar land. For them, it was a sanctuary of order amidst what they perceived as wilderness.

Yet, for Africans, these spaces stood as visible and daily reminders of exclusion and subjugation. The hotel and its rituals were emblems of a foreign domination that took their land, extracted their labour, and placed them at the margins of society. African workers were permitted within the hotel’s grounds only as labourers: porters, cleaners, cooks, and waiters. Their role was to sustain the comfort of others, their presence acknowledged only in service and their voices absent from the social life that unfolded around them. The grandeur of the White Rhino, to many Africans, was not a marvel but a monument to dispossession—a structure erected on the backs of their toil, yet one from which they were socially, culturally, and politically excluded.

The conversations that filled the lounge and verandas revolved around farming ventures, hunting expeditions, and colonial politics, with little to no acknowledgment of the African majority whose land and labour underpinned the entire colonial enterprise. In this way, the White Rhino Hotel became both a social hub and a quiet citadel of racial hierarchy, reinforcing the boundaries that defined colonial society and making clear the power relations of the time.

Built in 1927 by Alexander "Sandy" Herd, born on 15 August 1881 in Scotland, the hotel’s other investors included Berkeley Cole and Lord Cranworth. Yet it was Herd who managed the day-to-day affairs and who, among the settler community, earned a reputation for his unwavering honesty and sobriety. For African employees and observers, Herd was perhaps a fair-minded manager, but still a participant in a larger system that left Africans disenfranchised in their own land.

Berkeley Cole, meanwhile, was well known as the brainchild behind the Muthaiga Country Club, another symbol of settler exclusivity. It is said that, in a rare and rather uncharacteristic display of respectability, Cole confessed his growing discontent with the rough, uncivilised treatment he and his peers endured at the local club. He lamented that he was sick of being treated like a pig, subjected to the crude conditions of frontier life, and craved the dignity of a refined environment. He envisioned a sanctuary of civility, an establishment where the ruggedness of settler existence would be replaced by the elegance of British social rituals. In his imagined oasis, a gentleman could ring a bell, and a drink would be brought to him without delay—served with ceremony, on a spotless tray.

Both the White Rhino Hotel and the Muthaiga Country Club stood as architectural and social manifestations of the colonial desire not merely to survive but to thrive in dominion. They were not passive structures but active agents of exclusion, spaces where settlers performed their superiority, reinforcing the racial and social divisions that underpinned the colonial order. For the African majority, these institutions embodied the lived realities of alienation, dispossession, and indignity. They were daily theatres of racial privilege—gilded spaces from which Africans were barred, even as they maintained them with their labour.

The settlers who frequented these establishments—whether pausing at the White Rhino after a day managing coffee plantations or mingling at Muthaiga’s lavish cocktail evenings—depended on these spaces to affirm their precarious sense of dominance in a land that was never theirs. Here, deals were struck, alliances forged, and the myths of colonial adventure polished over clinking glasses and hushed conversations. Outside these walls, however, the African world watched and remembered, seeing in these grand buildings not symbols of civilisation, but monuments to their own exclusion.

Rafiki JK, excellent write-up; it's good to remind us where we came from. Did Princess Elizabeth spend her holiday at White Rhino or the Treetops still in Nyeri? Nyeri nearly became capital of Nairobi!. Keep up informing/teaching especially new generation 18-58 years old, where Kenya was those early years 1900-1963. Cheers.