The story of Kenya's forgotten World War II Italian prison near Oldonyo Sabuk

It was in this house where Italian Duke of Aosta, Prince Amedeo Savoia was kept to die

A few years back, a friend referred me to a massive bungalow near Mount Kilimambogo which I was told once belonged to the late American steel billionaire Sir Northrup McMillan, the founder of Juja Farm – and in whose memory the McMillan Memorial Library in Nairobi was erected.

By then, it was run-down house and only one of its 40-something rooms was under use by officials of Muka Mukuu Farmers’ Cooperative Society, a struggling coffee company on the verge of bankruptcy.

From where I sat on an old armless wooden office chair, I could see the valley below and the small dam that provided McMillan with water for his coffee farm and to his house – known for its wide range of visitors who were entertained and served here by groomed Somali girls.

The seat had seen better days exposing the sisal fibre used for padding – long before foam cushions came to the market. The floor had lost its subtle sheen – the golden years when it was polished to the standards of a billionaire and where former US President Theodore Roosevelt used to lodge during his poaching trips. Now all the rooms, but one, were empty though marked by spider cobwebs of intricate beauty and which brushed our face – when not careful. Rodents had taken over some rooms whose thick layer of dust had remained untouched for years.

Certainly, Muka Mukuu didn’t know the piece of history they were sitting on- or how much value they could get had they opened McMillan’s farm to agri-tourism. It was going to waste.

Why this house – even today - hardly attracts any tourists is for a simple reason: It has not been marketed and perhaps we hardly know its place in World War II.

McMillan had inherited a fortune of close to $8 million after the death of his father in November 15, 1901. He then started hunting safaris for museums in the US. That is before he settled in Juja and Kilimambogo.

The manager told me what he had gathered about the Kilimambogo house – most of it unsubstantiated rumours with little historical value. But something caught my attention. From where I sat, just below my feat, I could see the outline of an old trap door – its iron ring still in place. I asked if we could wedge the door open and he grudgingly agreed.

“There could be snakes inside there!” my photographer Rebecca Nduku warned me as the manager handed me a torch after forcefully opening the lid.

I went down the wooden staircase – by then I had no phobia for snakes - and crawled towards the direction of horse stables for a few metres before I hit a dead end. Part of the tunnel had collapsed and certainly, there were no snakes. As I gathered later, the tunnel must have been sealed deliberately and for a reason.

If you look at Winston Churchill war papers starting May 19, 1941 this Kilimambogo house starts featuring. It was on that date that the British War Cabinet was told that the Italian Duke of Aosta, Prince Amedeo Savoia-Aosta (below), who had been appointed by Benito Mussolini – the man who led Italy into the Second World War- to become the commander-in-chief of the Italian forces in East Africa.

Amedeo had surrendered marking the end of a bitter war with Britain which was actually led by the Kenya African Rifles (KAR). His surrender at Amba Alagi and with full honours is still celebrated in military circles and he is deemed a hero by Italians.

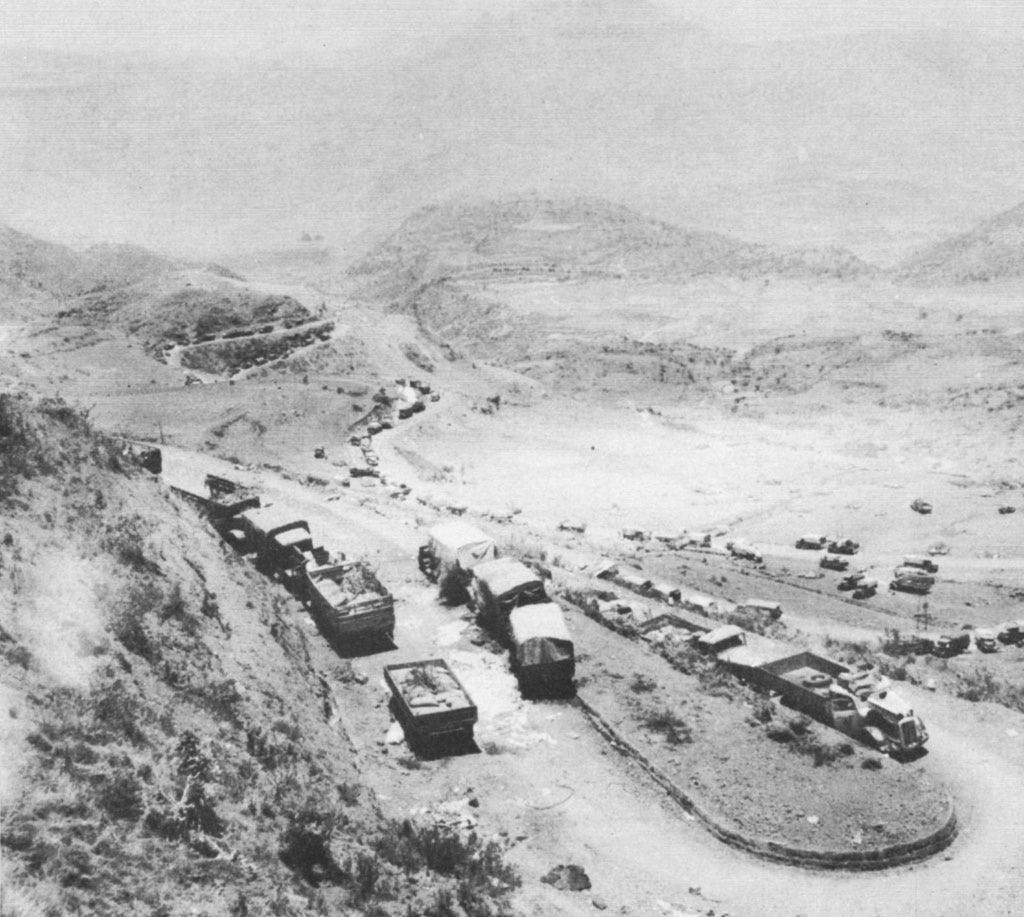

Italian vehicles abandoned in Amba Alagi

When soldiers surrender will full honours, they are allowed to keep their side arms. The rank-and-file troops are permitted to keep their personal possessions and march out in formation and with their flag before they are officially paroled. Senior officers are allowed to keep their ranks.

See Youtube video here:

From Kilimambogo, he commanded the Italian prisoners of war in Kenya. It is estimated that Kenya hosted between about 55,000 Italian POWs who were held in 11 camps spread throughout the country. But Prince Amedeo was basically in charge of the units in Thika, Juja and Nyeri.

At Camp 360 in Ndarugu Thika, Prince Amedeo’s soldiers built a little church in the valley which is still in use today by the local Presbyterian church. Although this church (below) has been declared a national monument and is officially known as the old Italian Church, there is very little literature about its place in Kenya’s history and has been eclipsed by the small size Italian church in Mai Mahiu along the old Nairobi-Nakuru road largely maintained by a Nairobi businessman Francis Mburu.

Camp 360 Church in Ndarugu, Thika

Still in the vicinity is the other memorial left behind by Amedeo’s soldiers – a stone pillar in Kalimoni Juja which has also been gazetted as a national monument. Another monument left by Camp 360 Ndarugu is the Brick Manufacturing Plant inside Thika Prisons which few Kenyans know about.

Also, records show that there was an attempt to use the POW to build a new railway line connecting Thika with Garissa but after a few kilometres this idea was shelved.

If the Kenya Tourism Board (KTB) had a wish of promoting Italian tourism in this country, the prisoner of war camps and their history would be a strong starting point. Also, perhaps the Kiambu county government would want to rethink tourism sites in this county.

On the wall of the Kilimambogo house, the Italian embassy in Nairobi erected a plaque to honour the house where Prince Amedeo was brought and placed under house arrest until his death at a Nairobi hospital on March3, 1942 – after contracting malaria which was aggravated by an old tuberculosis of the lung.

And that could be the reason that the escape tunnel that was built by McMillan in his house was sealed. But by the time we visited, we noted that the exit to the tunnel had remained near what were the horse stables and we were told – which I doubted - that in case of any attack, McMillan would have escaped towards the stables, taken a horse and fled in his buckboard.

Those who have read about McMillan know that he was “over 20 stones” (over 128 kilograms) and at the National Bank of India (the modern-day Kenya National Archives) the bank had a special chair for him as a customer. Certainly, he would not have fitted the tunnel under his house and why it led to the stables is still not clear. In future, that tunnel should be re-opened.

Students of history know much about the Italian campaign in Northern Ethiopia but few would think that Kenya was the holding centre for thousands of Italian prisoners. For record, the Duke of Aosta had led the Italian advance into Sudan and Kenya and the invasion of British Somaliland from June 10, 1940. As the commander in chief of the Italian forces in the region, he became the most celebrated prisoner of war and that is why the Kilimambogo house if of immense historical importance. When he died, a prisoner world newspapers covered the story widely (see below)

Some of his soldiers were buried inside the Italian War Memorial Church in Nyeri which is only used once in a year. Located along Ihururu road about five kilometres from Nyeri Town, it houses some 676 Italian POWs.

At the front of the simple wooden pews and just about the altar is the marble-lined tomb of the Duke of Aosta – buried here together with soldiers he gallantly led.

So interesting! I direct a project on Contested Histories (www.contestedhistories.org) in The Hague that looks at monuments, buildings sites, etc., dealing with complicated and controversial historical events and figures from the past. I believe this building might make an interesting case study. I'm glad a teacher in Kenya alerted me to your interesting article.

Best,

Marie-Louise Jansen

Thank you for this article. I lived in Eldoret for a few years and loved the place!..