The Stanley Hotel: Empire, Elegance, and Exclusion in Colonial Nairobi

The Stanley Hotel is more than a historic building—it’s a map of colonial power

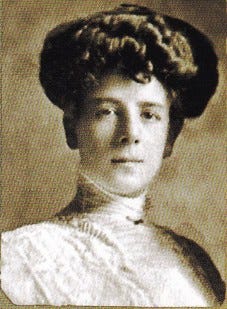

To understand the Stanley Hotel is to understand how colonial space worked. It wasn’t just a hotel; it was an instrument of empire. And at the heart of it stood a woman named Mayence Ellen Woodbury—a milliner from London who stitched her name into the story of Nairobi’s rise from a railway outpost to a settler city.

Mayence Woodbury arrived in Nairobi at the turn of the 20th century, drawn by the opportunities of a new colonial frontier. A talented dressmaker, she started small—sewing garments, managing a general store, and renting out rooms above a shop. But she had bigger dreams. In 1904, she opened what would become the Stanley Hotel, Nairobi’s first “real” hotel, made of corrugated iron and timber, but with enough charm to attract railway officers and colonial administrators.

She was ambitious, resourceful, and resilient. When the original hotel burnt down in 1906, she simply pitched a tent and kept taking in guests. That spirit of adaptability would define her career—but it also reflected the logic of the empire: occupy, rebuild, expand.

By 1913, Mayence and her new husband, Frederick Tate, had launched the New Stanley Hotel at the corner of what is now Kimathi Street and Kenyatta Avenue. It wasn’t just bigger; it was a statement. Designed by British architects, it came complete with a Bechstein piano, a billiards table, and plush furnishings meant to transport guests back to the comforts of England.

But this wasn’t just about elegance—it was about exclusion.

In colonial Nairobi, spaces like the Stanley were reserved for Europeans only. Africans were welcome as staff but not as patrons. This racial boundary was both unspoken and deeply enforced, turning the Stanley into a literal and symbolic fortress of white privilege. It separated not just bodies but experiences—marking who belonged in the heart of the city, and who did not.

It’s easy to forget that Nairobi’s early years were structured by a rigid racial order. The Stanley was part of that architecture. It offered comfort, yes—but only to a select few.

Mayence’s own story is a paradox. As a woman in a deeply patriarchal settler society, she defied convention. She wasn’t merely a hostess; she was a businesswoman, a property owner, and a shaper of urban life. Yet her ability to succeed was also made possible by her whiteness. While most African women were restricted to domestic labor or informal trade, Mayence could build an empire—literally and socially.

She turned femininity into a business model. The Stanley offered a space of gentility and refinement in a town known more for mud, malaria, and railway dust. It was a haven for men in the colonies, yes—but it was also a projection of a certain kind of imperial femininity: tasteful, organized, and powerful in its own right.

Mayence lived through wars, revolutions, and the decline of the empire. She died in 1968, just a few years after Kenya’s independence. The hotel survived her, and today it remains one of Nairobi’s most iconic landmarks.

But its legacy is more than just historical. The Stanley is a living monument to colonial privilege, one that has seamlessly transitioned into postcolonial capitalism. Its guests have changed, its uniforms updated—but the aura of exclusivity remains. And like many colonial relics, its story is told without always acknowledging who was left out of its glory.

What of the African cooks who toiled in its kitchens? The porters who carried luggage up creaky staircases? The workers who polished its floors before dawn? They are mostly nameless in the official histories, yet they were the backbone of its success.

The Stanley Hotel is more than a historic building—it’s a map of colonial power drawn in wood, iron, and imported linen. It reveals how cities like Nairobi were built not just with bricks but with ideas of who deserved luxury and who was meant to serve. It shows how gender, race, and class intersected to shape not just individual lives, but entire urban geographies.

Today, when you sip tea at the Stanley’s Thorn Tree Café, it’s worth asking: Who was allowed to dream here? Who got to rest? And who kept the lights on?

JK excellent up-date. I like it. So when are we having tea/coffee for old times sake- New Stanley of 1960s?-DaveM

Important knowledge for all Kenyans. Our history is sophisticated and quite interesting