From Hola to Homa Bay: A Legacy of Lies, Brutality, and Police Impunity

The killing of Albert Ojwang exposes a familiar cycle.

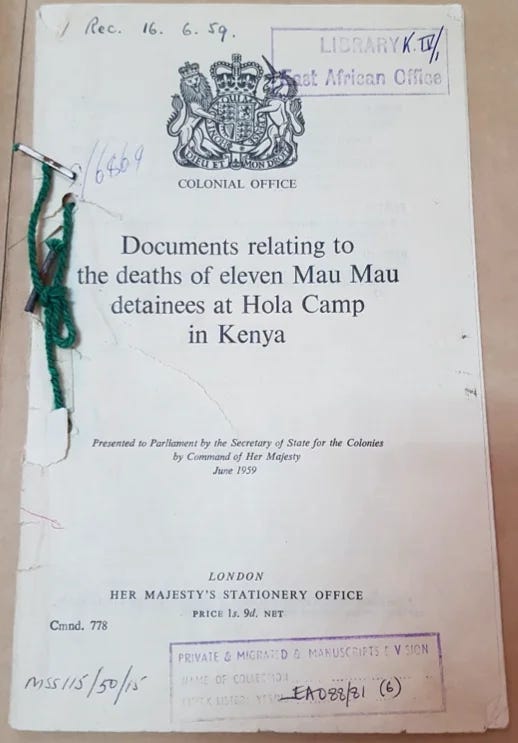

After the Hola Massacre in 1959, the colonial administration told the world an unbelievable story—that eleven Mau Mau detainees, whose skulls had been crushed and limbs broken, had died from drinking contaminated water. It was a grotesque fiction, a calculated lie meant to shield the state from accountability and preserve the illusion of British civility. The truth—later confirmed by a colonial inquiry—was that these men were beaten to death by camp warders under official orders. It was not an accident. It was murder, and it was covered up.

More than six decades later, the same script continues to unfold in Kenya. The case of Albert Ojwang (below), allegedly killed by police officers and whose death is now shrouded in official silence, reminds us that state violence did not end with independence. It merely changed uniforms. From the dungeons of colonial detention camps to the police cells of today, the tactics of repression—extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and lies—have endured.

Extrajudicial killings in Kenya are not isolated incidents. They form part of a brutal architecture of state-sanctioned violence, especially against the poor, the outspoken, and the politically inconvenient. Victims are often labeled as gangsters, terrorists, or threats to “peace and security.” Families are left to collect bodies from mortuaries, bruised and riddled with bullets. Investigations rarely yield truth or justice. Instead, the state responds with silence—or worse, propaganda

.

From the mysterious deaths of activists like JM Kariuki in the 1970s to the assassinations of politicians like Robert Ouko in the 1990s, to more recent killings of rights defenders, lawyers, and civilians in informal settlements, the Kenyan state has repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to use lethal force—and a mastery in burying the truth. The Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA) was created to restore public confidence, but even it often finds its hands tied by political interference, fear, or lack of cooperation from within the police ranks.

The cover-up is not just in the lies told but in the institutional culture of impunity that ensures no one is held accountable. Officers accused of murder are transferred rather than prosecuted. Witnesses disappear. Inquests stall. The cycle repeats. The message is clear: police violence is not only tolerated; it is systemically enabled.

Albert Ojwang’s case, if left unresolved, will join a long list of names etched into Kenya’s grim history of state violence. But it does not have to. If history is to stop repeating itself, then truth must be told, and justice must be demanded—not as a favor from the state, but as a right owed to every citizen.

Until then, the stench of Hola’s contaminated water will continue to waft through our present—a metaphor for the official lies we’re still being asked to swallow.

Absolutely! It’s what Frantz Fanon wrote about in his book, “Black Skin, White Masks.” The colonizers didn’t leave Africa; they turned Black and continued the oppression. It will take another revolution for the total emancipation of the Black people in Africa and the diaspora. Fortunately, more and more people are standing up against the lies after every death. Compare that with the time Ouko was assassinated.

Hola's Contaminated Water! Thank you for writing this piece and reminding us of the history - lest we forget.